As we approach local elections in England and Wales on 2nd May 2024, local and national politicians are setting the priorities for local authorities: for the funding they receive and spend – and the services they spend it on.

Where are responses to domestic violence and abuse in these priorities?

With many local authorities struggling to cover their statutory duties, such as social care and child protection, and facing loud criticism over bin collections and potholes, where do domestic abuse services fit into their plans?

These plans matter – from advice and information services, to specialist refuges and accommodation: all these are services that national government has devolved to local decision-making.

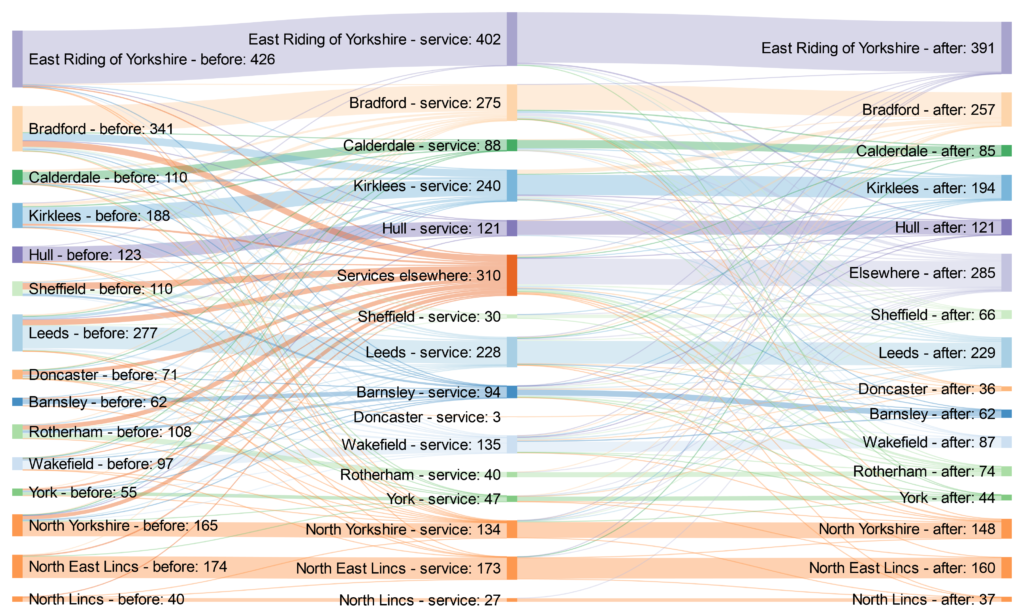

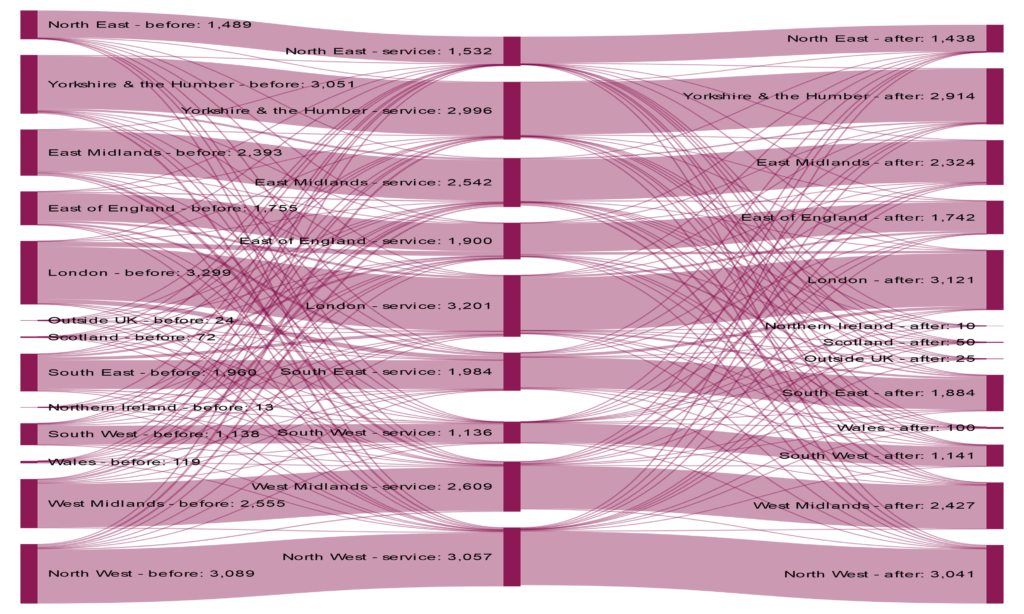

But domestic violence and abuse isn’t local. Not only are men violent and abusive to their women partners in every local authority in the country… but, to escape that threat, many women and children cross local authority boundaries to seek help and support – as well as safety.

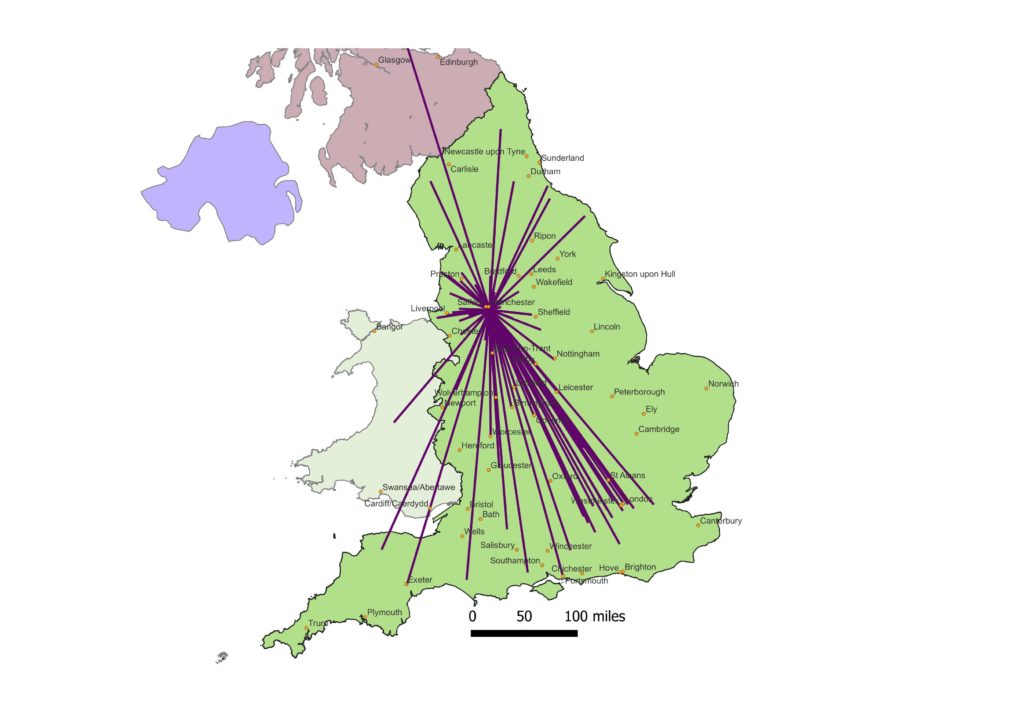

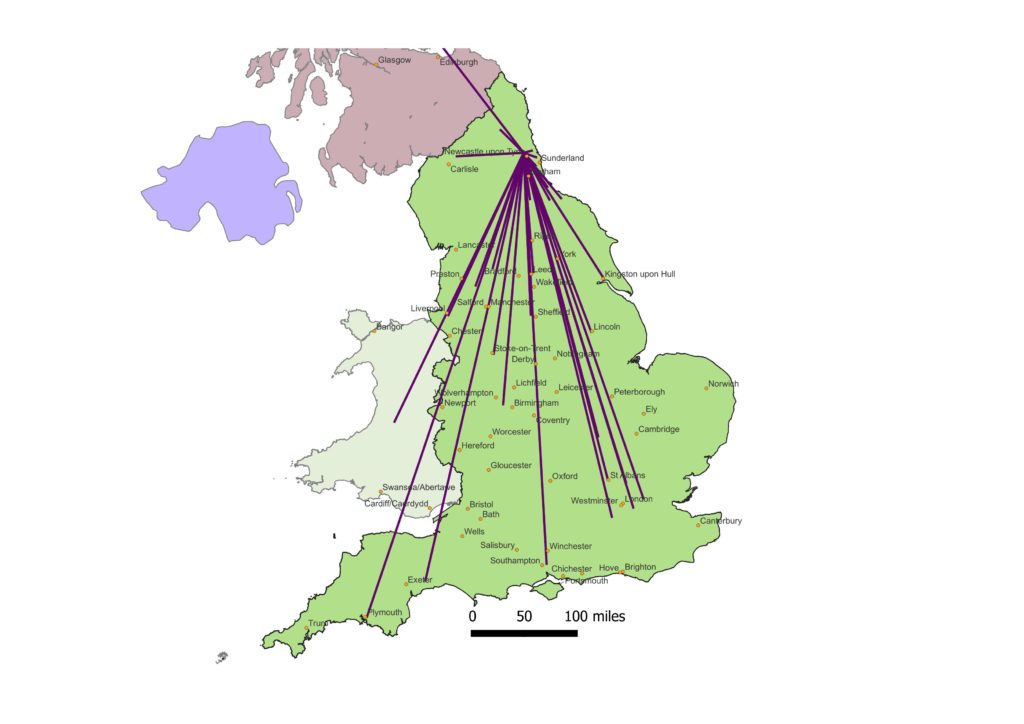

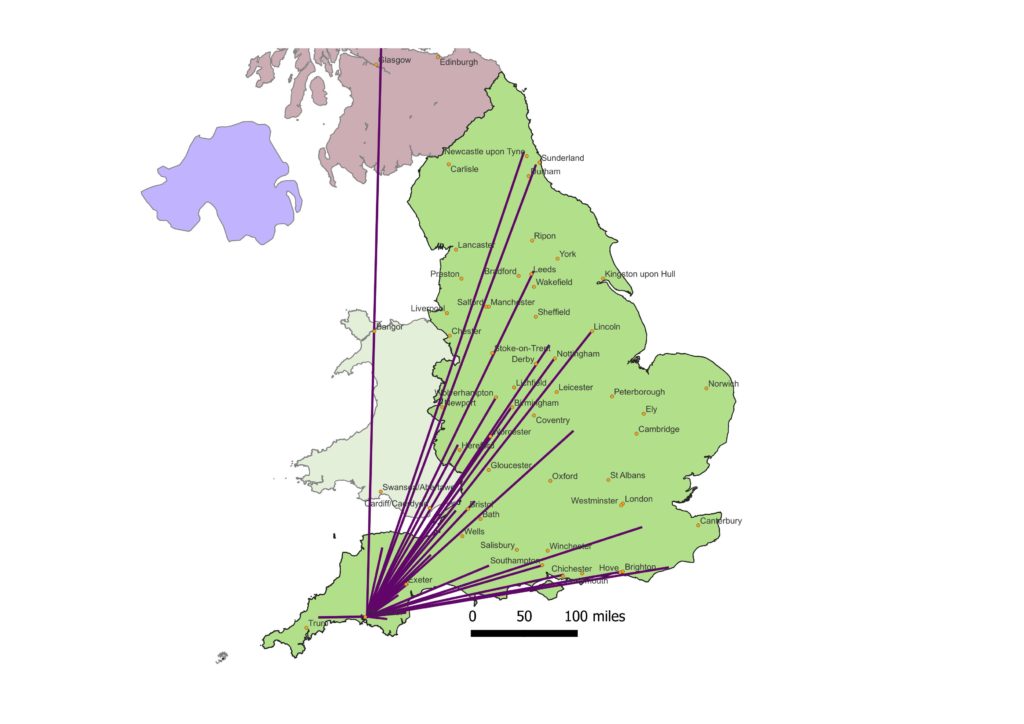

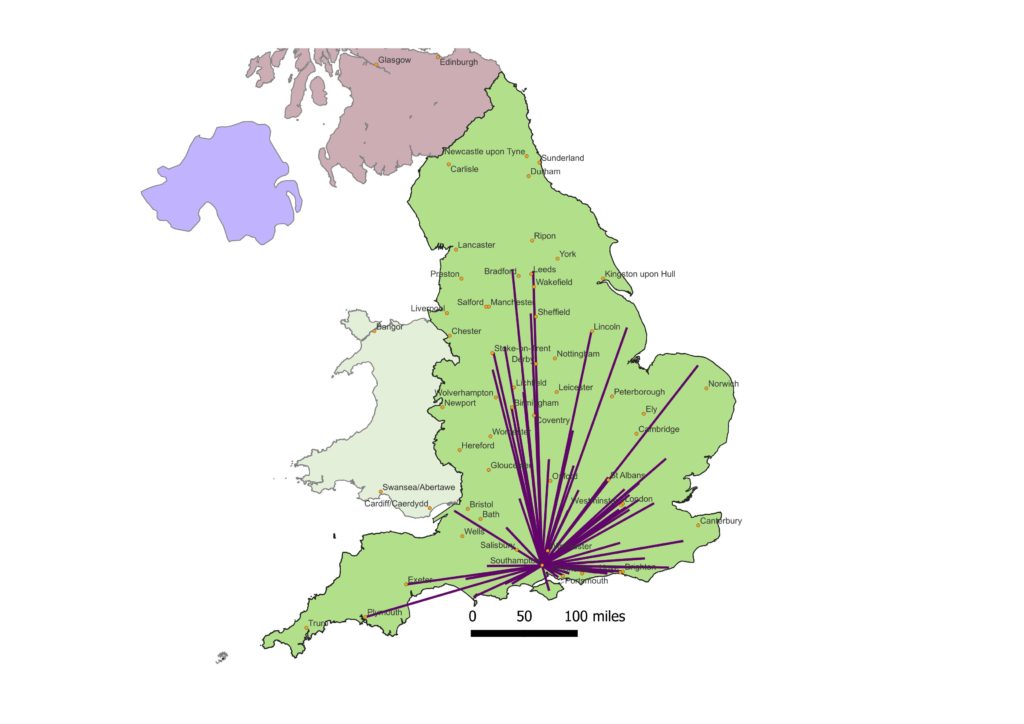

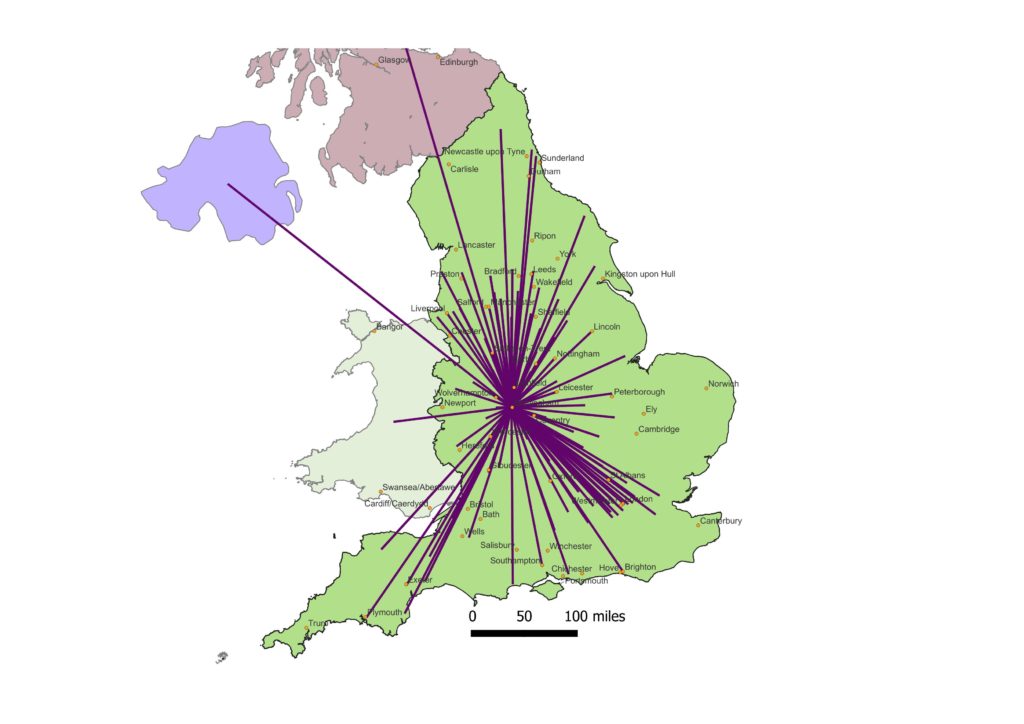

The maps show the domestic violence journeys in one year to services for just five cities, as women (often with children) travel to or from Manchester, Newcastle, Plymouth, Southampton and Birmingham. They show women having to leave their local authority to get the help they need.

But women and children can only make such journeys if the services exist.

Local politicians may pledge to fund – or to cut funds to – domestic violence services, as part of seeking votes in the May elections. It’s a patchwork of separate – unconnected – decisions. And decisions that do not only affect local voters – but affect the tens of thousands of women and children who end up needing services somewhere else – not in their original local area.

It’s an ongoing mismatch between the scale of need and the scale of response – further cemented in the Domestic Abuse Act 2021.

We need services everywhere, because perpetrators are abusive to their partners or ex-partners everywhere; but we need a network across the whole country – not at risk from hundreds of separate local cuts and local priorities.