Whenever we hear of cutbacks or closures to domestic violence services in a particular area, we hear campaigners and concerned local people ask “Where will local women and children go now – when they need to escape abuse?”

But if the service under threat is a women’s refuge, then local women and children will probably be the least affected.

Local women and children will most likely be going to a refuge elsewhere.

Cuts and closures of local support services affect local women and children. But – if they need the distinctive services of a refuge – chances are they would not have been able to stay in their local area anyway.

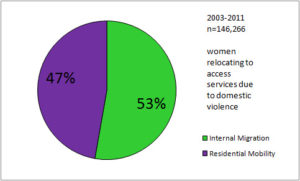

In general, when women relocate to access services because of domestic violence, it’s about half-and-half whether they stay in their own local authority area (“residential mobility”) or move to another local authority (“internal migration”).

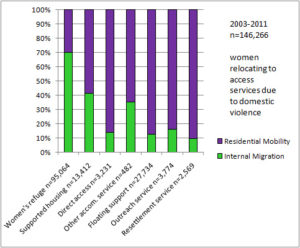

But, this varies enormously between types of services. For support services that do not provide accommodation 80-90% of women are from the local area; and for non-refuge accommodation around two-thirds are similarly from the local area.

However, for women’s refuges, 70% of women have travelled from another area.

Women’s refuges are not really local services[1].

But – at present – they are generally planned and funded locally, which makes them particularly vulnerable to cutbacks. And local cuts do not primarily have a local impact – they affect women and children nationally. We are planning and funding refuges at the wrong scale.

Local women and children everywhere might need women’s refuges; but they need them not in their original local area.

[1] Bowstead JC. 2015. Why women’s domestic violence refuges are not local services. Critical Social Policy 35: 327–349