The concept of Journeyscapes in this research is that the response to domestic abuse needs should be at a functional scale and capacity – a practical and accessible infrastructure for women and children. That should be a fundamental responsibility of the state – of Government – in response to the human rights violation of violence against women.

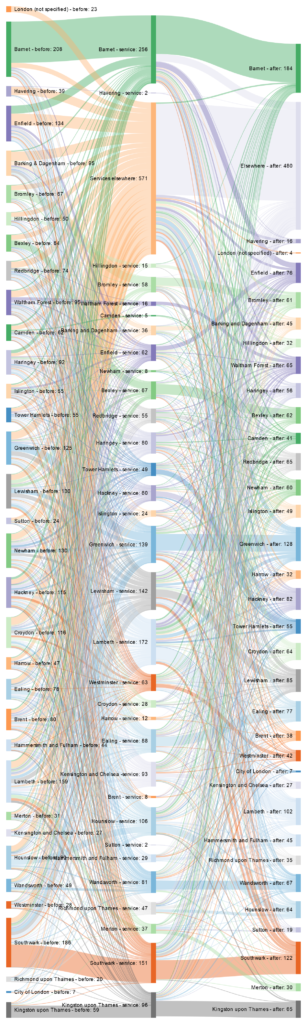

Whilst Government persists in devolving responsibility to local authorities – not least in the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 – women and children in their tens of thousands are crossing these local authority boundaries to seek help. Yet again, the scale of the response does not match the scale of the need.

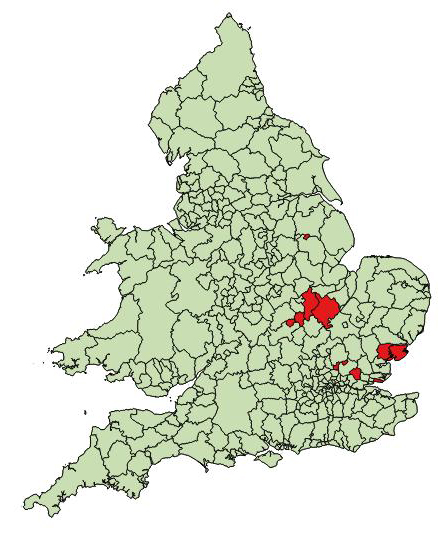

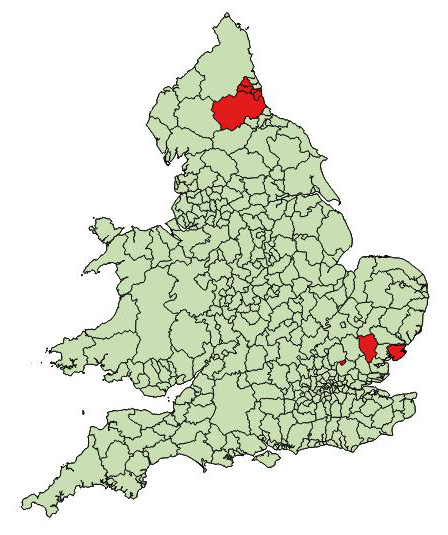

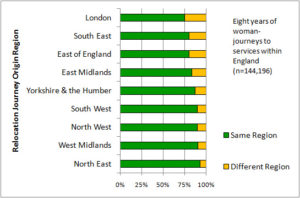

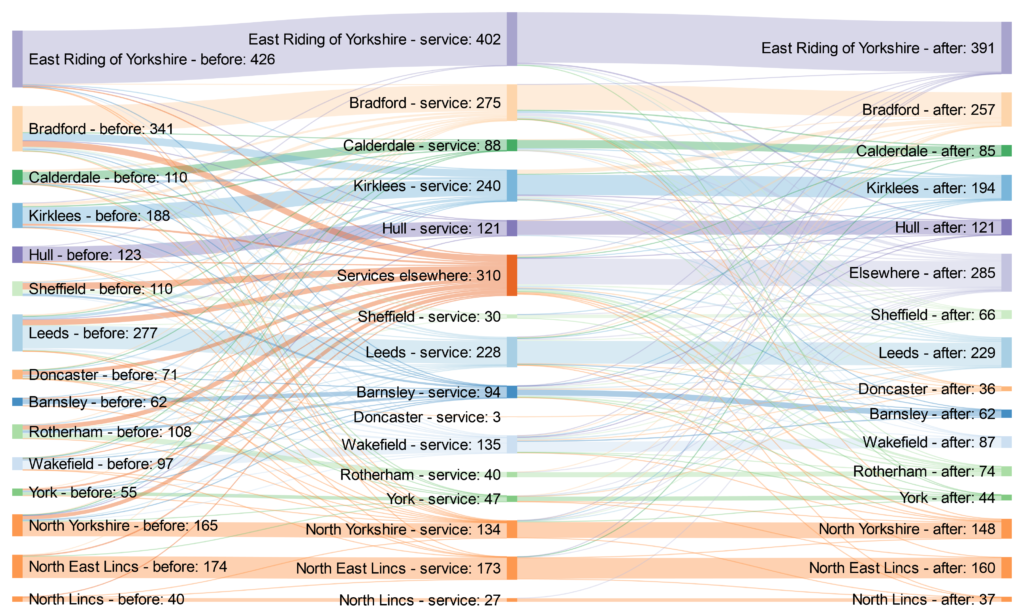

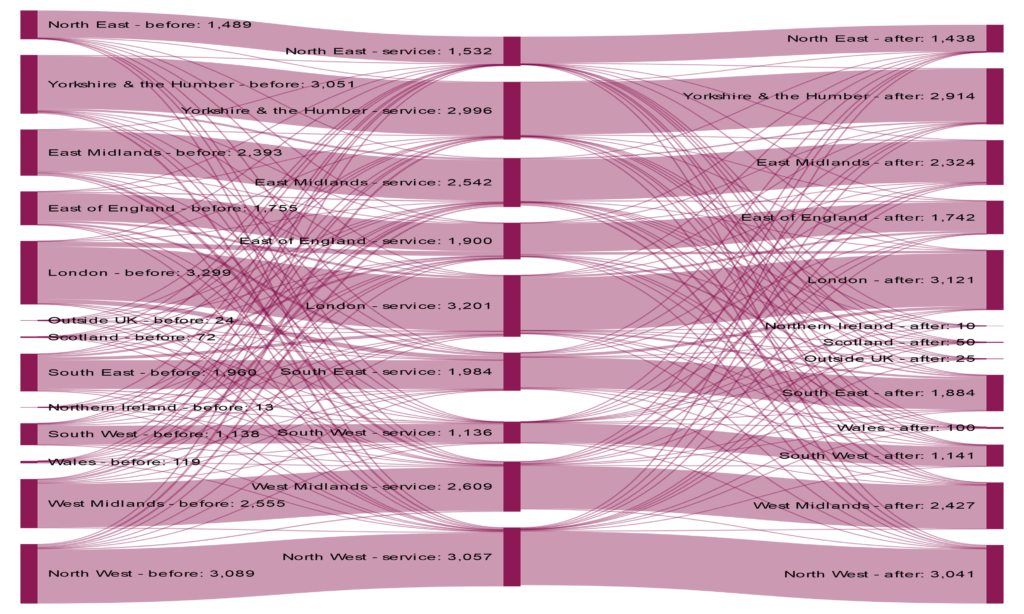

A new open-access article[1] from this research shows that the regional scale in England is much more self-contained than local authorities in terms of accessing services; but this is not currently a scale of service commissioning. The example of the region of Yorkshire and The Humber shows women relocating to access a service due to domestic abuse; and many relocating again when they leave the service: either to another local authority in the region, or to elsewhere in England.

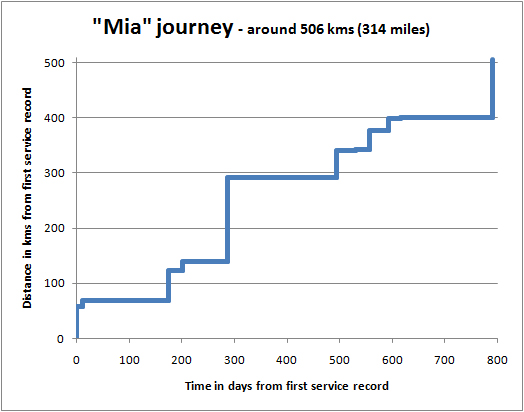

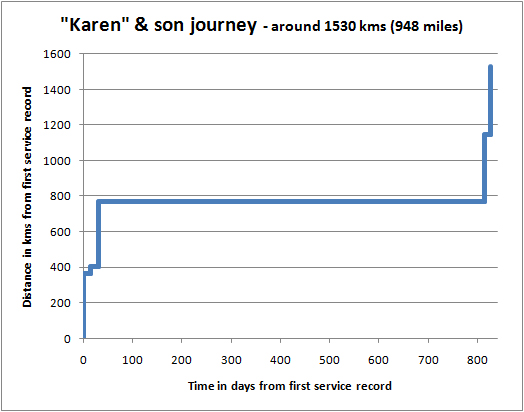

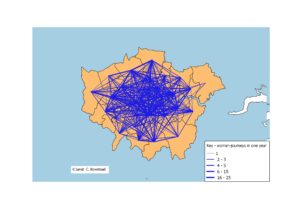

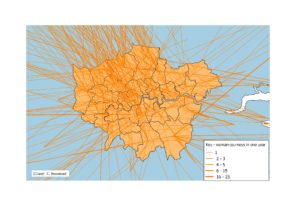

The churn of all these journeys is striking.

But, looking at the flows at the regional scale, rather than the local authority scale within a region, shows a different pattern. Though there are clearly domestic violence journeys leaving each region, the majority stay within the same region.

The journeys may be forced by the threat of the abuser – or by the policies and (non) availability of services at the point of seeking help. Some journeys would not be necessary if the support was better, and if perpetrators were held responsible for their abuse. But the reality is that these journeys are made.

If Government wanted to meet the needs of these journeys, then it would ensure that there were no additional barriers put in place across local authority boundaries: that the state wasn’t making anything worse. A rights-based, needs-led service provision would plan at the national scale for sufficient and sustainable service capacity, without any access restrictions in terms of past, present, or future location.

A human rights argument would be for all options to be possible without any additional harm or losses being caused by the state in terms of policies, laws, and services.

As Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in the UK, the state should have duties to minimise individuals’ losses, and support their rights and resettlement. Women and children should be enabled to journey as far as they need, and stay as near as they can, with the role of the state authorities being to journeyscape (by law, policy, and provision) an otherwise potentially hostile terrain.

[1] Bowstead, Janet C. 2022. “Journeyscapes: The Regional Scale of Women’s Domestic Violence Journeys.” People, Place and Policy. doi:10.3351/ppp.2022.8332428488.