We encounter statistics every day – numbers that provide evidence about life and society, both for interest and argument, and as the basis for policy and political decisions.

But where do they come from? – and where do they go to?

Statistics can have such a powerful influence on what services are provided – and to whom – on funding, and on cutting funding… on government across the board.

In the United Kingdom, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) is the main producer of official statistics, and is independent of Government ministers to try to ensure that its statistics can be relied upon and believed. But it has recently been criticised about the quality and trustworthiness of its statistics, and responded with plans to improve its core economic surveys.

It is not just the economic surveys that cause concern – and all statistics should be engaged with critically, considering how they were produced and any limitations in methods.

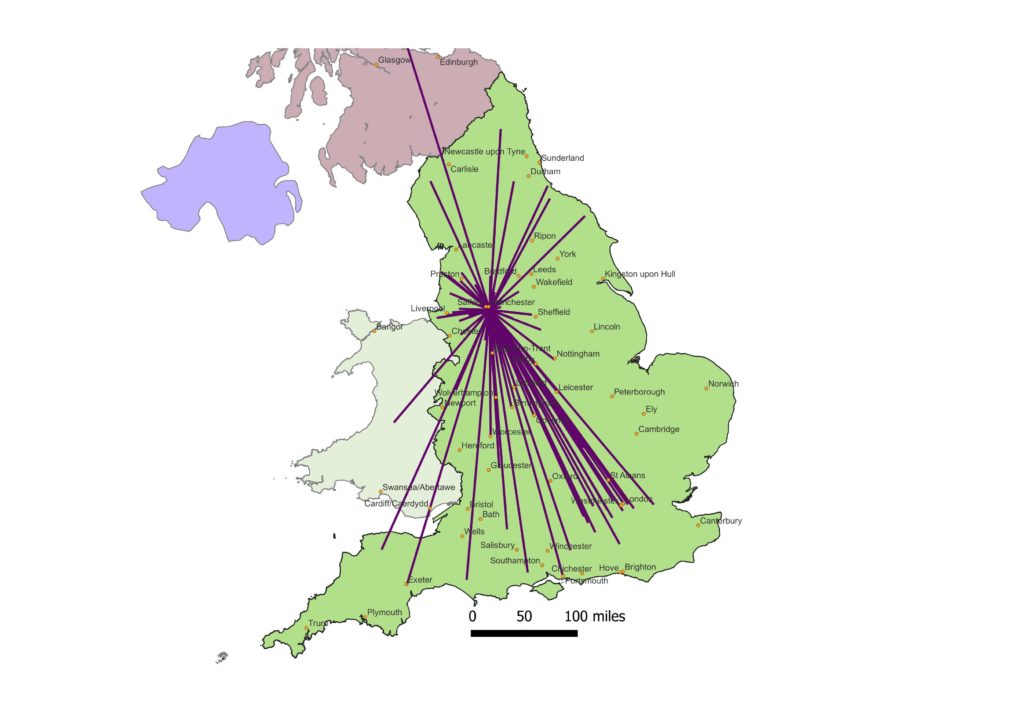

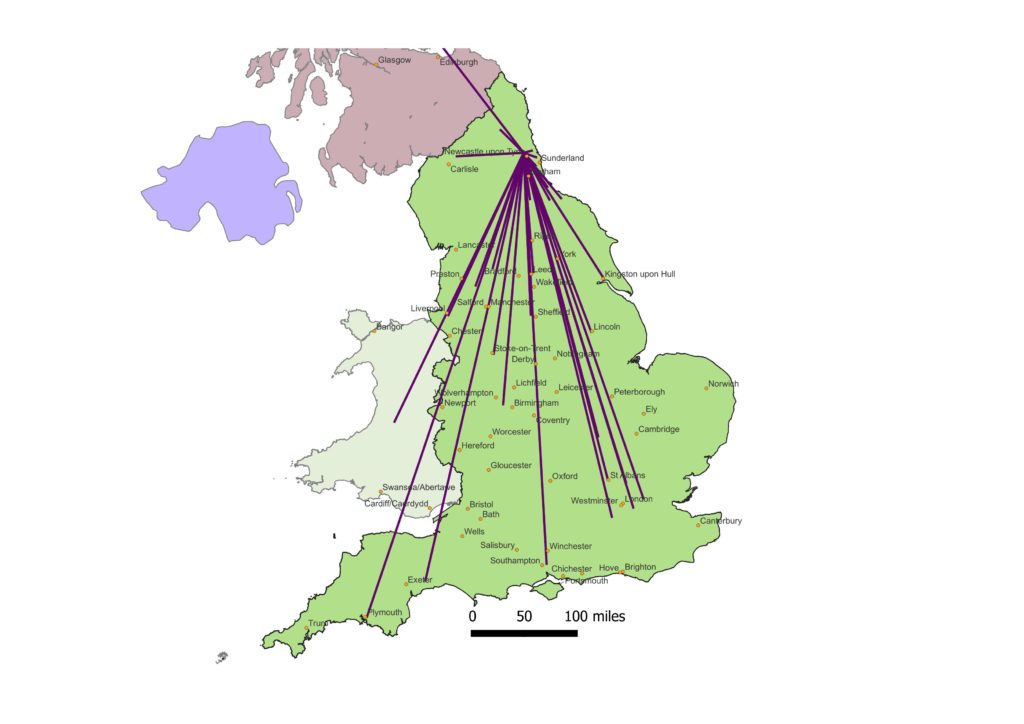

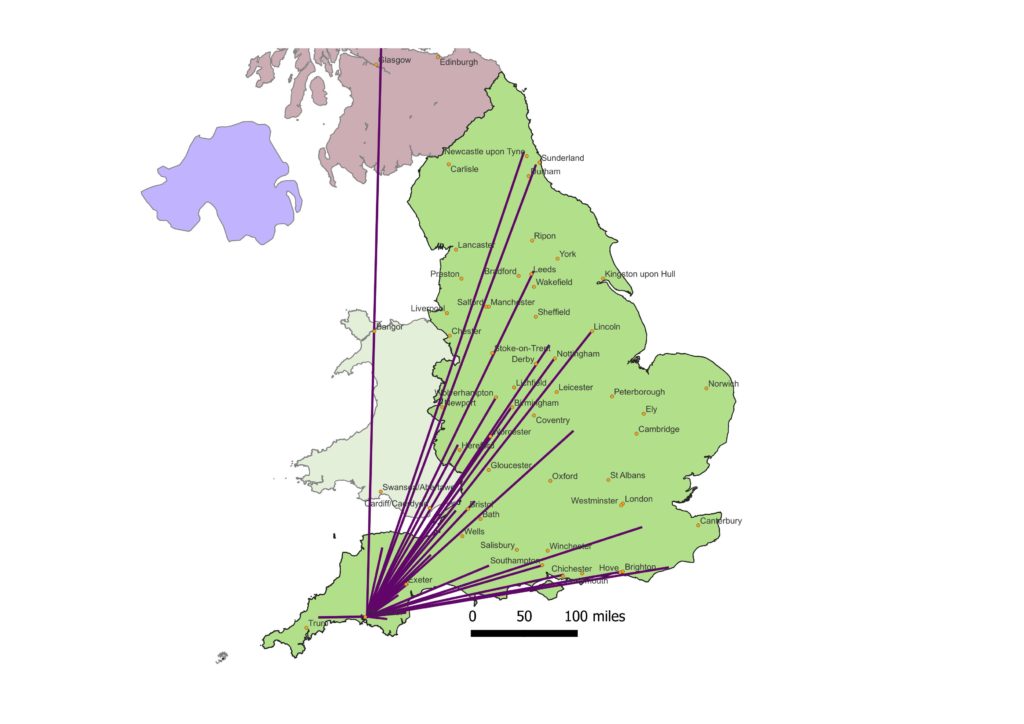

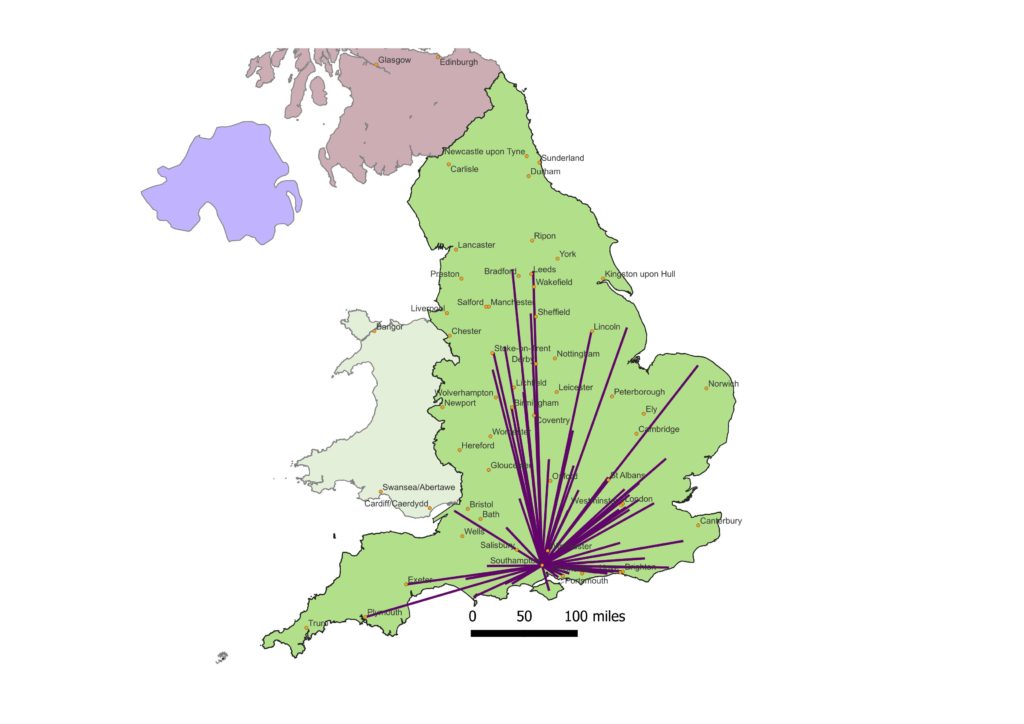

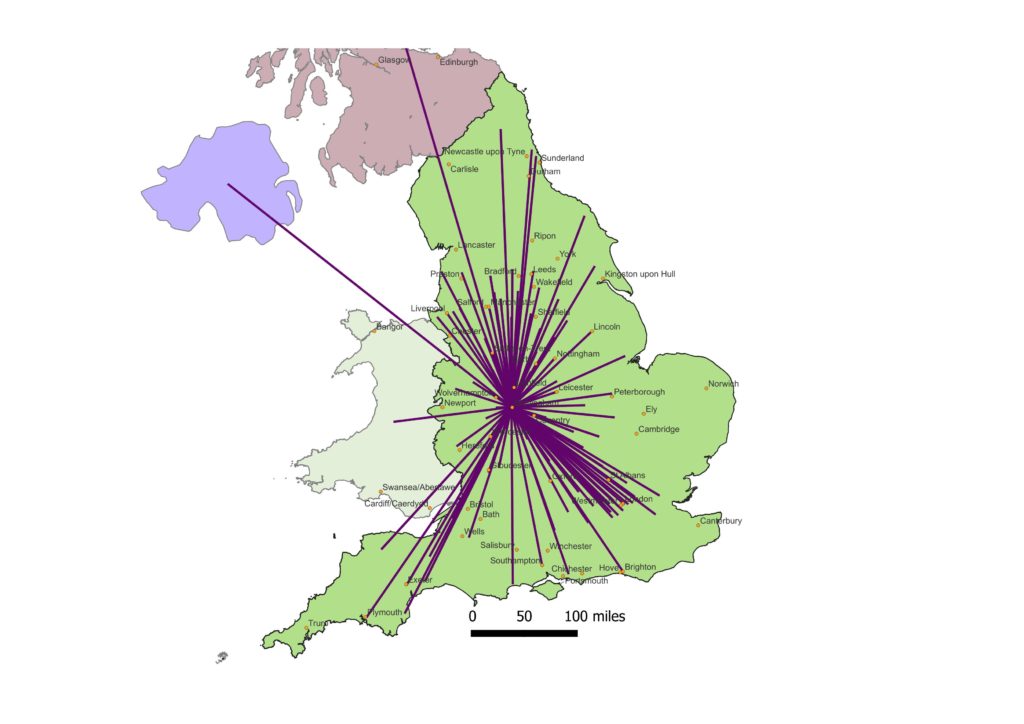

This research project on women’s relocation has long raised the issue of the sampling frame of social surveys. The ONS focuses on the settled population in private households, with little consideration of the implications of excluding the unsettled population…

Annually, the ONS produces an overview of domestic abuse statistics without addressing the issue of the population on the move; and presents its data as if it proves whether domestic abuse is decreasing or increasing.

It does not.

The Radical Statistics conference last year focused on sampling inadequacy – and the Radical Statistics Journal has just been published including an article which discusses the issue of excluding from social surveys those who are forced to be on the move due to domestic abuse.

The article shows that the ONS should not be complacent about the implications of excluding the unsettled population from its social surveys – and it shouldn’t only be thinking about its economic statistics in terms of the urgent need for improvement in quality and trustworthiness.