Domestic violence abusers will use any means they can to control their partner and limit her freedom. Socially powerful men will use their position – historically think of King Henry VIII being able to have two of his wives killed for him with impunity. Other abusers may try to harness the power of the state in lesser ways – such as repeatedly reporting their (ex)partner to the police, or the courts, or report her missing (rather than the reality that she has escaped…)

The increasing power of technology in everyone’s lives can give perpetrators another whole range of tools to abuse, to control, and to track down a partner who tries to escape.

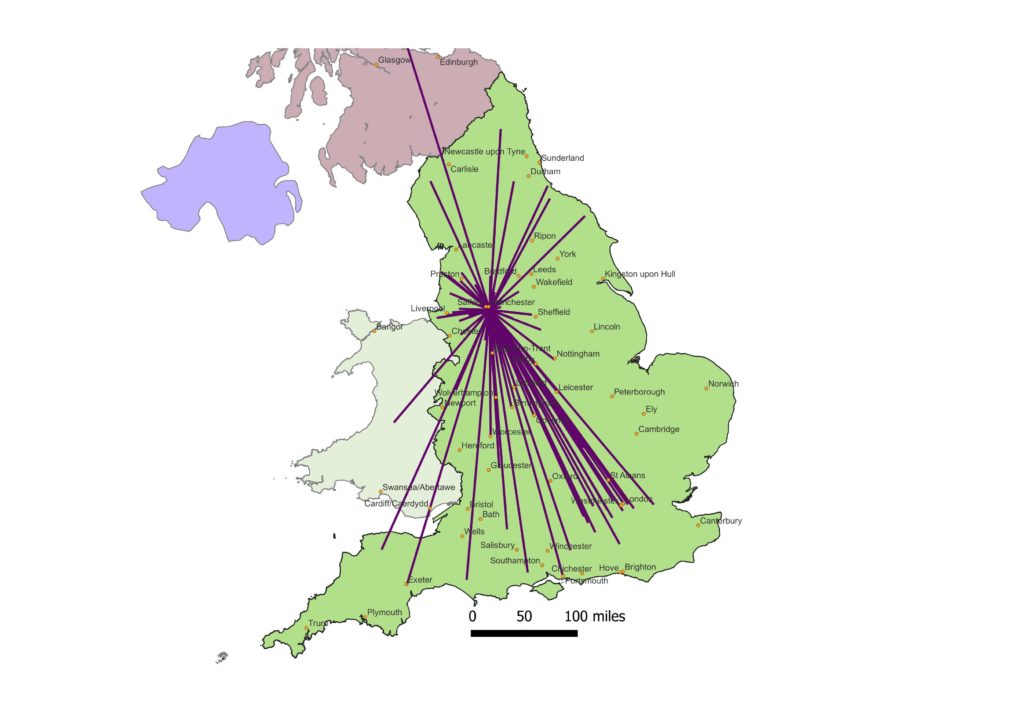

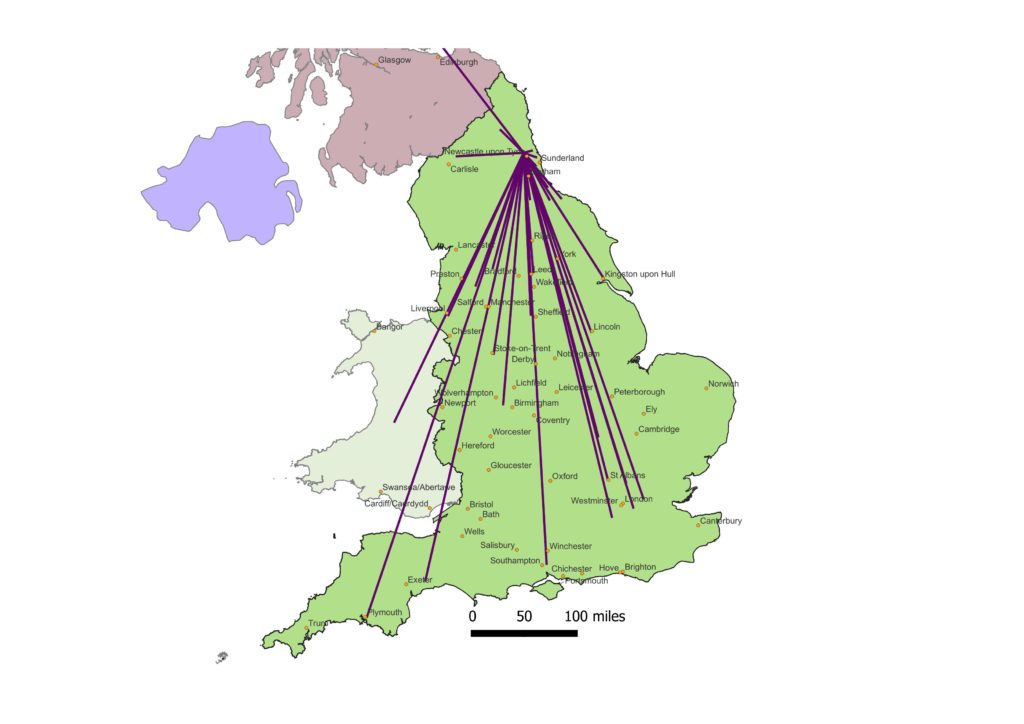

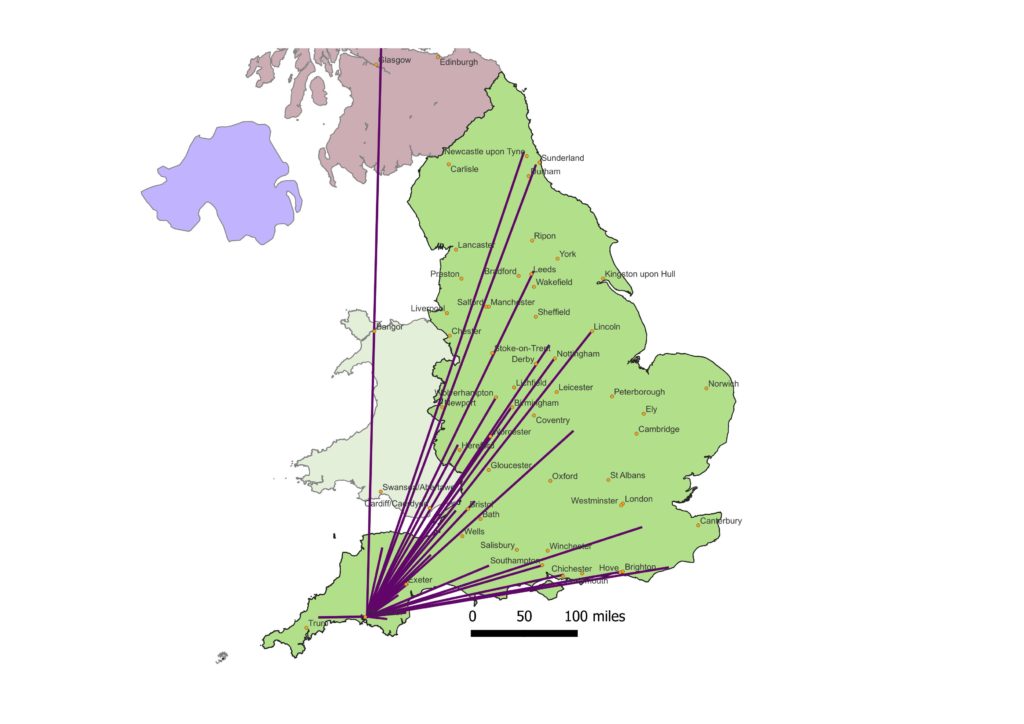

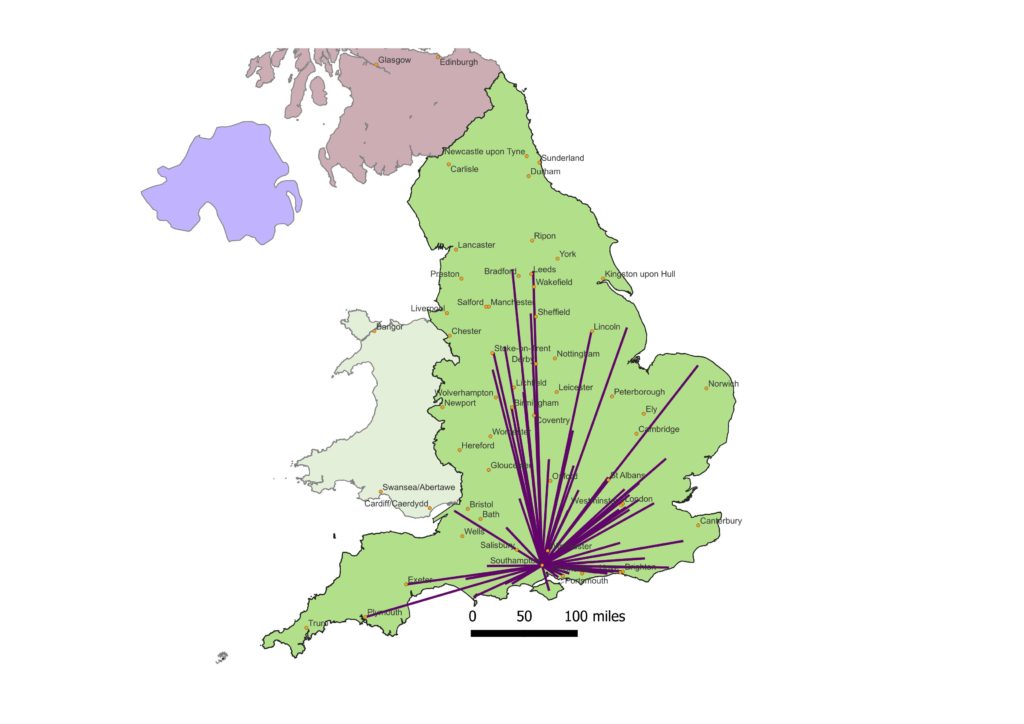

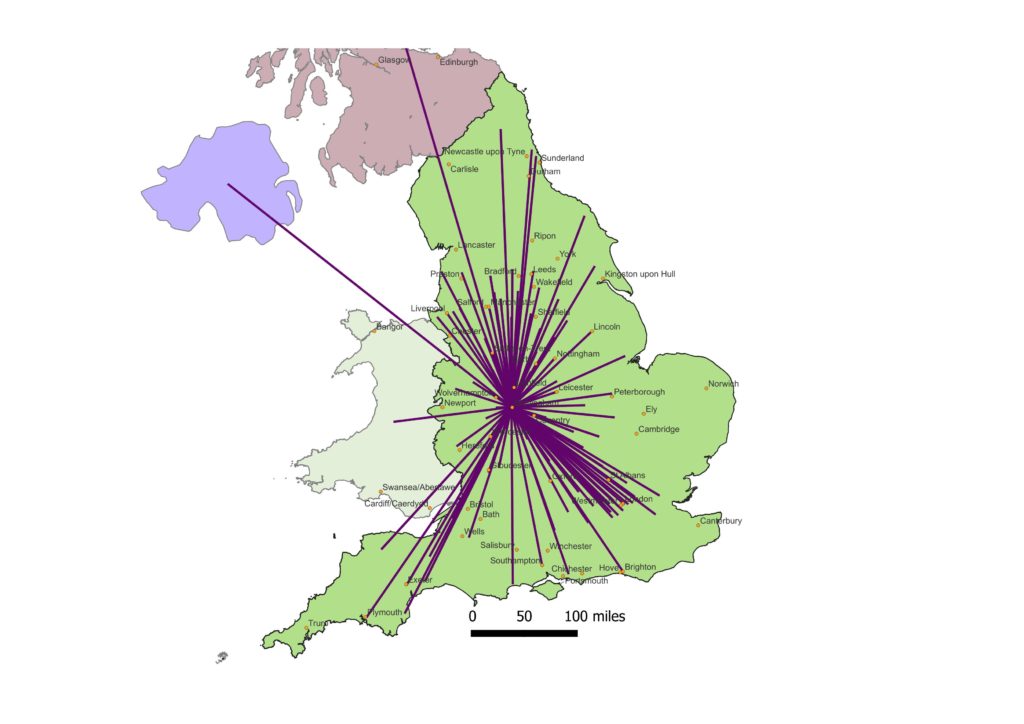

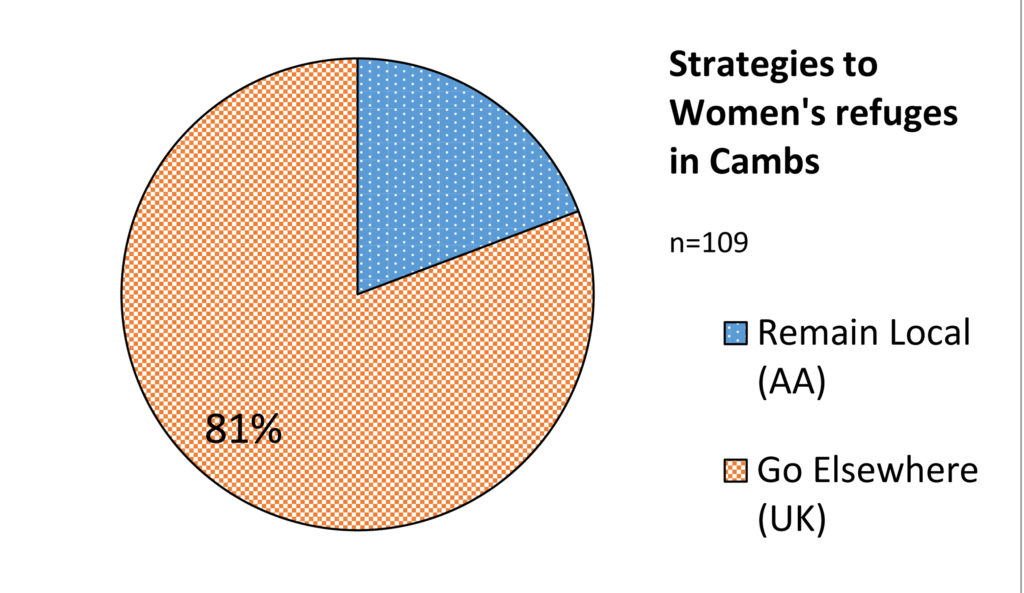

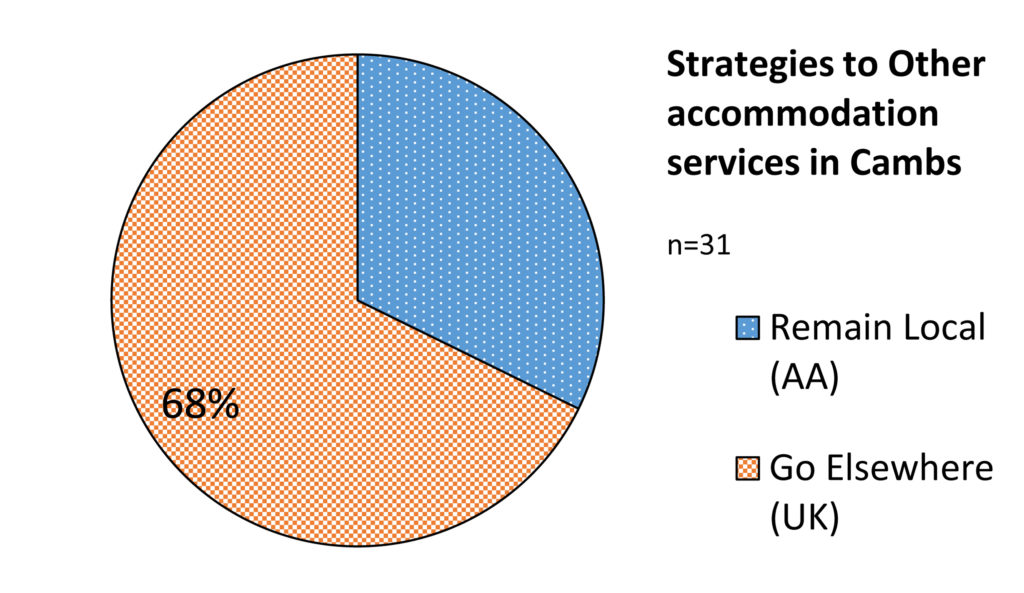

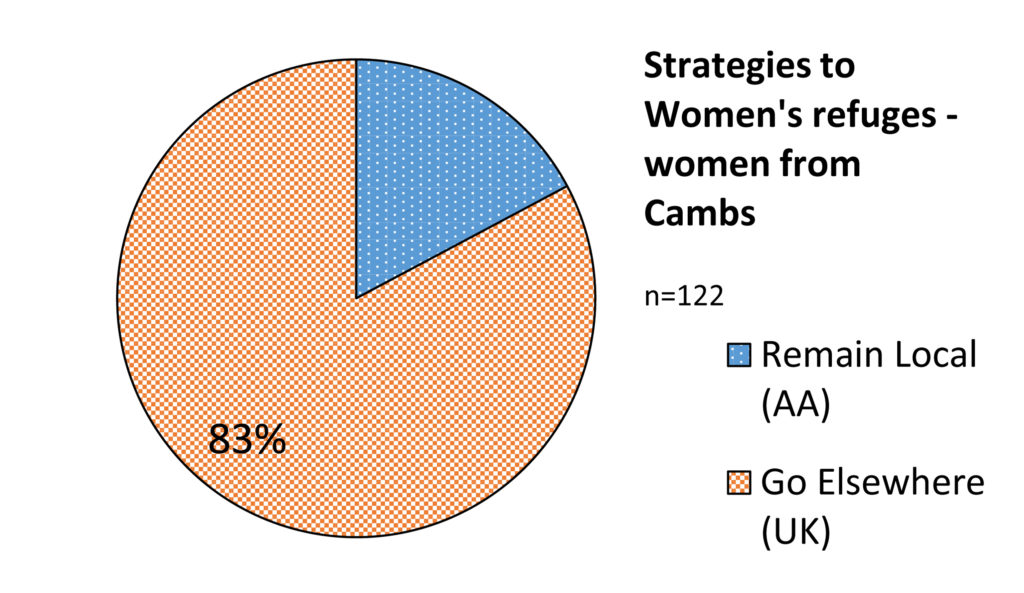

This research focuses on the geographical journeys women and children make to escape violence and abuse – how distance can enable safety, as well as – of course – causing intense disruption in survivors’ lives.

But technology can bridge those distances – and breach that safety…

In the early stages of this women’s journeyscapes research, Louise spoke about her ex-partner:

“he was following me with my phone – leaving messages, texting – just saying – you’re going to make it worse on yourself, you better come back, blah, blah, blah. And I just ignored the messages – and some of the messages that he was sending that was horrible, I’m sending to his mum – to show her what he was sending me. And she just basically said – you’re doing the right thing, just – you know – just ignore it.”

Even as she was on a coach from Wales with her young daughter and escaping towards London, the perpetrator was somehow still travelling with them via her phone.

Technology has developed in scope and sophistication since then – providing even more power in the hands of abusers.

A recent presentation focuses on “dual-use” technologies – such as Smart Doorbells, Pet/Baby-Monitoring Cameras, and Location-Tracking Apps. Technology that can both increase safety and increase risk…

Across the world, people are waking up to the risks and dangers of technology, with many studies of perpetrators’ use of technology to abuse: such as examples from Sweden to Australia to Canada, as well as many reports and articles from the UK.

The new Violence Against Women and Girls Strategy for the UK includes in its Action Plan recognition of the need to face up to the risks of “dual-use” technology by highlighting the need for:

“Work across government on what more we can do to encourage ‘safety by design’ of smart and connected technology to better protect victims and survivors and help stop perpetrators using this type of technology to further their abuse.”[1]

It has always been known that perpetrators of domestic violence will use any means they can to continue the abuse – over time, space, cyberspace and distance – meaning that we all need to be ever more careful with each new technology they can use as a tool to abuse.

[1] Page 7: UK Government. 2025. Freedom from Violence and Abuse: A Cross-Government Strategy to Build a Safer Society for Women and Girls: Volume 2 – Action Plan. CP 1450-II. London: UK Government, December 18, 2025. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6943d5f0fdbd8404f9e1f2a4/31.260_VAWG_02_Action_Plan_template_FINAL_WEB_171225.pdf