For women who have experienced domestic abuse, the front door is a powerful image of whether they feel safe or not. Living with an abusive partner, they feel unsafe to go into the place that they had called home. The danger is inside – not in the outside world – and home feels like a prison.

As Elizabeth said in this research, after she had left her violent husband:

“I’m in a different world – completely! I’m free. I feel like I’ve come out of prison in a sense; where I was completely dictated to – now I’m free! If I want to go down town – I go! If I want to stay out all day – I can. I’m not controlled – I’ve got the control; I’ve taken the control back!”

The front door became an image of independence – as Elizabeth said:

“I’ve got my own front door – so what if I can’t afford the curtains! [laughs] I’m safe – you know – I’ve got my life back.”

Having left the violent relationship – a front door you feel safe to go through is a definition of a true home. As Julien Rosa said:

“You don’t need to be scared to go in – you just go in. You know, when I was back in [the relationship] I used to be scared to go in – I just stood there. So – that’s a big difference – to be happy, to be relaxed – it’s incredible.”

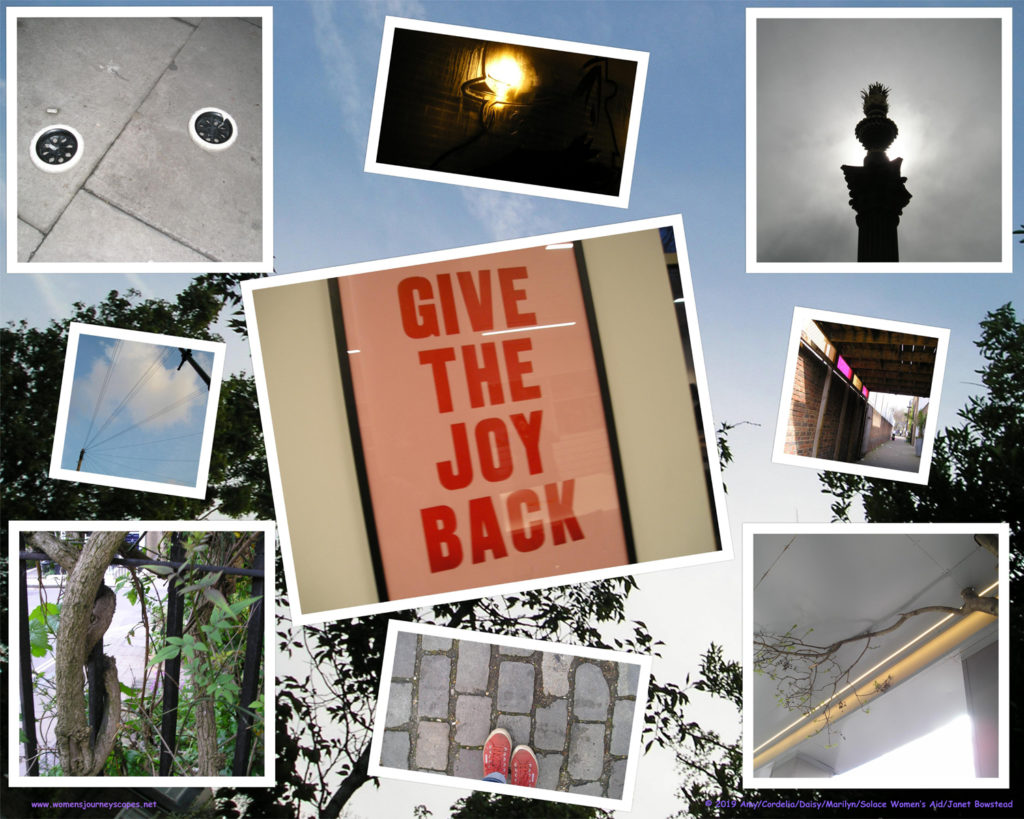

The participatory creative work in this project provided time and space for women to communicate such experiences. Women in the groups drew ‘maps’ of their journeys, and took photographs to explore the twists and turns of their routes.

This short video shows some of their images and captions about opening the door towards a new life. Their images show closed doors, gates, blocked views, difficult routes and strange angles that mirror the disorientation of abuse. But they also show a way forward and the hopefulness of a way through.

Women saw the support of others as part of opening the door towards a new life – and wanted to communicate that way forward to other women escaping abuse.