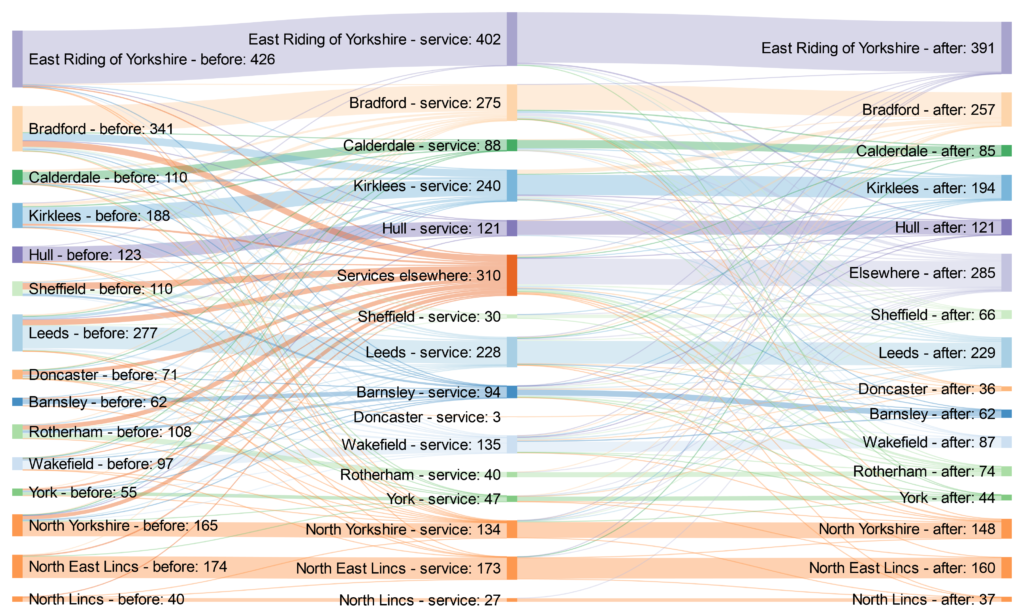

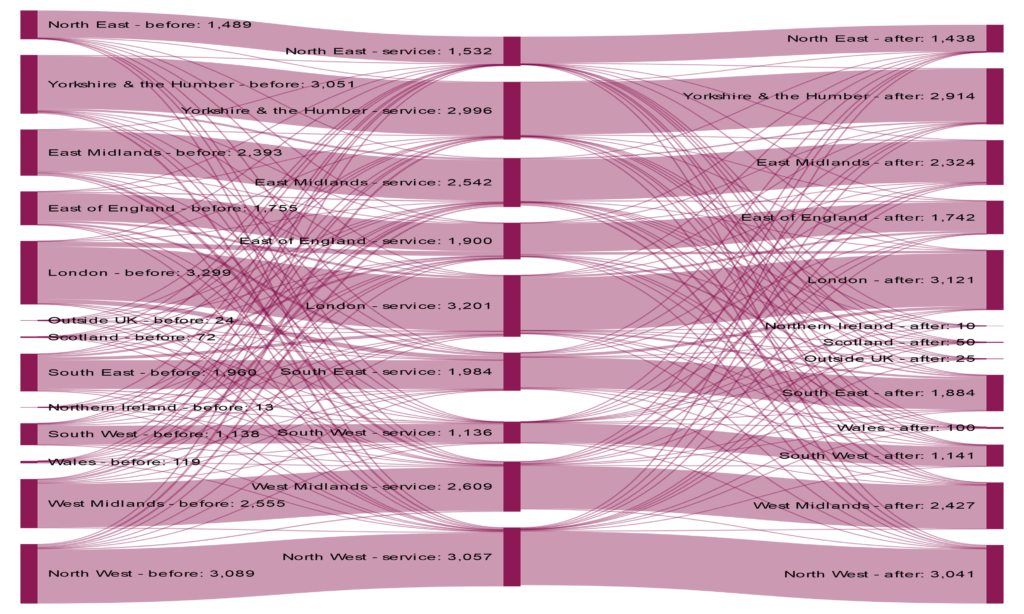

Despite decades of recognition that domestic abuse forces journeys across local authority boundaries, and the further evidence of the scale of such journeys from this research, so many aspects of the system of services and support remain fragmented down to the local authority scale.

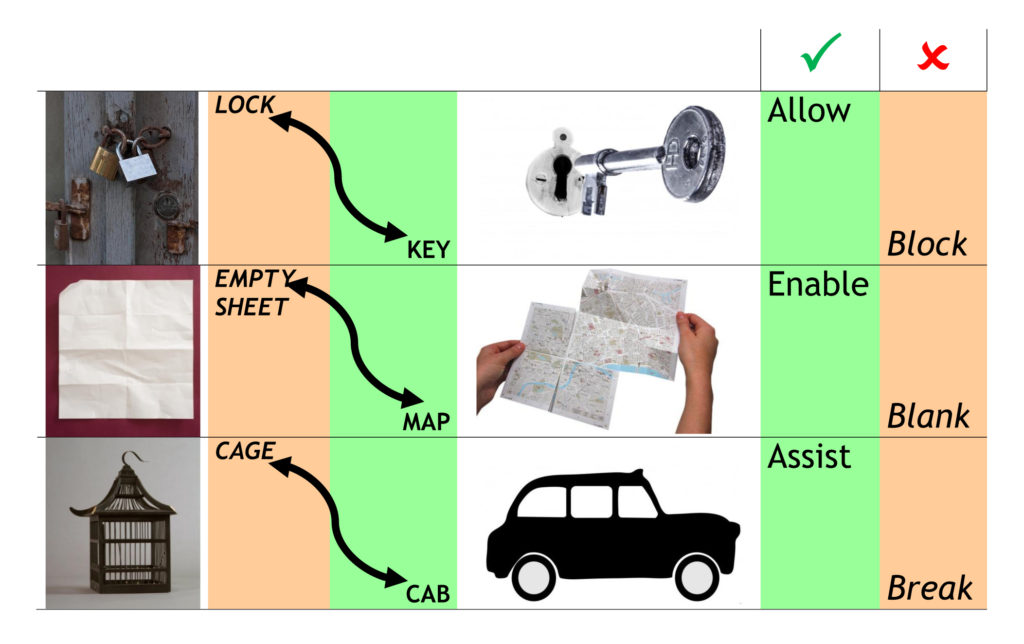

Local authorities can tend to operate as closed systems – like they are surrounded by moats to cut them off from everything else. As soon as you cross that boundary, everything changes – your rights to services, your place on waiting lists, your housing, schooling, college access, and so much else.

Government has further reinforced these boundaries – deepened these moats – by the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 devolving needs assessments and strategies for safe accommodation to the local authority scale.

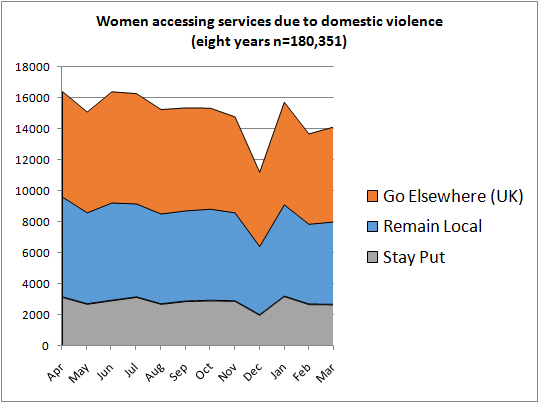

Yet tens of thousands of women and children have to move to a different local authority due to the violence and abuse.

And the problem isn’t just at the crisis point of seeking emergency accommodation – it continues when women try to find housing where they can resettle longer term, and find themselves caught out by residency requirements that they cannot fulfil. The drawbridge that let them cross to another place in emergency, is pulled up again when they try to apply for social housing, and they are turned away.

In 2018 statutory guidance was issued[1] because – to quote – “The government believes that victims fleeing domestic abuse should be given as much assistance as possible to ensure they are able to re-build their lives away from abuse and harm.”

But this clearly isn’t working.

Now the Government has realised that “domestic abuse victims are being denied social housing allocations in some areas because they have no local connection to an area” and identifies the need “to consider further measures beyond statutory guidance”[2]. The proposed solution for England is “to introduce regulations so that local authorities would be prevented from applying a local connection or residency test to victims who have been forced to flee to another local authority district in order to escape domestic abuse.”

But it wants to find out whether this is a good idea.

So there is a consultation at present[2] – until 10th May 2022 – asking local authorities and individuals about what is currently happening, and what the Government should do about it.

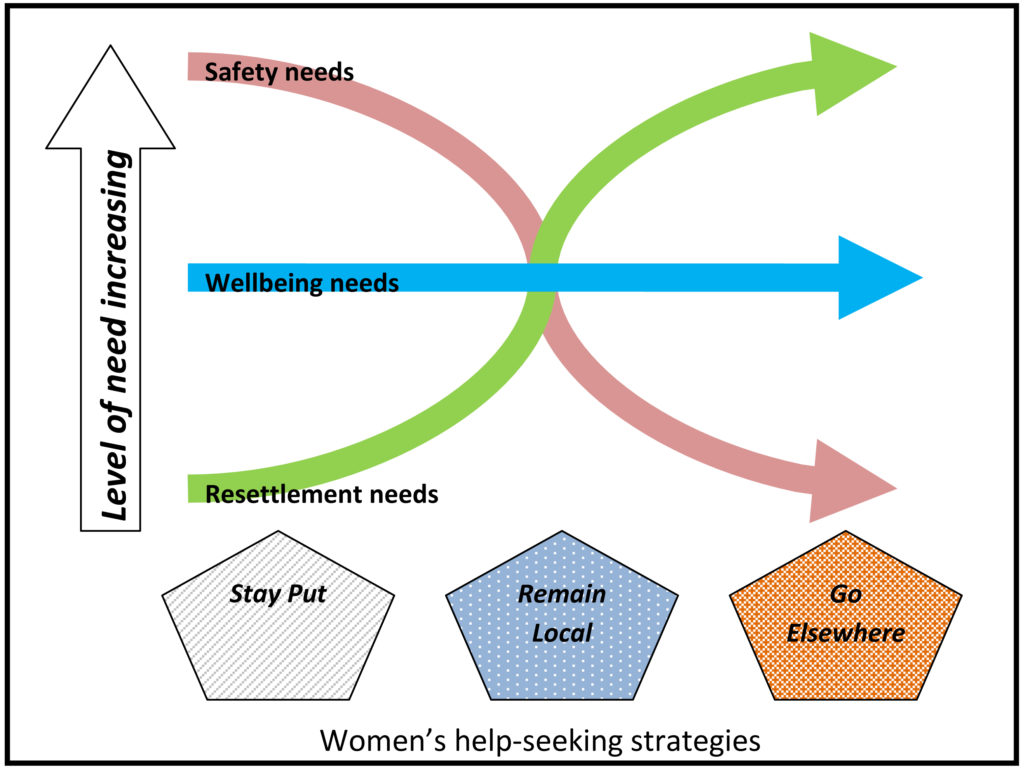

Women fleeing domestic abuse are fleeing a human rights violation: they should be able to stay as near as they can, or travel as far as they need, without being forced any further, and without any detriment to their lives.

But many of the consultation questions are not concerned with enabling rights and support, but are concerned that any change should be strictly limited. Proposed limits include that exemption from ‘local connection’ only applies for a limited time period “after the victim has fled domestic abuse” or that the social housing is only being considered “for reasons connected with that abuse”. The consultation asks about limiting it in terms of the current accommodation (eg. refuge, temporary accommodation, private rented), in terms of moving to England from the rest of the UK, and in terms of the kind of evidence of domestic abuse that local authorities require.

The consultation recognises the tensions between neighbouring authorities currently providing different levels of services, and pleads “We wish to see local authorities working together with neighbouring authorities”.

But nothing is proposed to make this happen.

Yet again, Government is not considering the larger scale over which tens of thousands of women and children travel – and is not taking national responsibilities – but is hoping that local authorities will make boundary-crossing work a bit better for a limited number, within limited circumstances.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/improving-access-to-social-housing-for-victims-of-domestic-abuse

Statutory guidance: Improving access to social housing for victims of domestic abuse

Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, 10 November 2018

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/consultation-on-local-connection-requirements-for-social-housing-for-victims-of-domestic-abuse

Consultation on local connection requirements for social housing for victims of domestic abuse

Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 15 February 2022